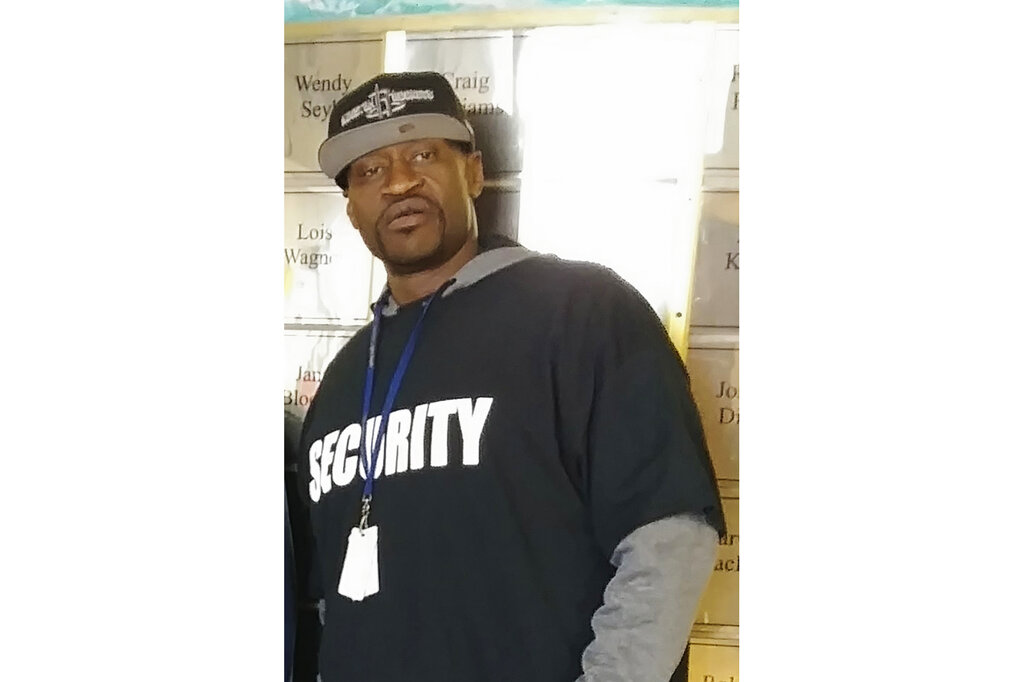

FILE – This undated file handout photo provided by Christopher Harris shows George Floyd. The message from protesters around the United States is that George Floyd is the latest addition to a grim roster of African Americans to be killed by police In demonstration after demonstration, protesters are carrying signs that include the names of other blacks whose lives ended violently in encounters with police. (Christopher Harris via AP, File)

The memorial services to honor George Floyd are extraordinary: three cities over six days, with a chance for mourners to pay their respects in the communities where he was born, grew up, and died.

But so are the circumstances surrounding them: Since his May 25 death in Minneapolis, Floyd’s name has been chanted by hundreds of thousands of people and empowered a movement. Violent encounters between police, protesters, and observers have inflamed a country already reeling from the coronavirus pandemic.

The organizers of the memorials want to acknowledge the meaning Floyd had in life to his large family and the broader meaning he has assumed in death, which happened after a white officer pressed a knee into the handcuffed black man’s neck for several minutes even after Floyd stopped moving and pleading for air.

“It would be inadequate if you did not regard the life and love and celebration the family wants,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton, the civil rights leader who will eulogize Floyd in two cities. “But it would also be inadequate … if you acted as though we’re at a funeral that happened under natural circumstances.”

“The family is not independent of the community,” he said. “The family wants to see something happen.”

The first service will be Thursday afternoon at North Central University in Minneapolis. Sharpton, founder of the National Action Network, and Floyd family attorney Ben Crump will speak.

Floyd’s body will then go to Raeford, North Carolina, where he was born 46 years ago, for a two-hour public viewing and private service for the family on Saturday.

Finally, a public viewing will be held Monday in Houston, where he was raised and lived most of his life. A 500-person service on Tuesday will take place at The Fountain of Praise church and will include addresses from Sharpton, Crump, and the Rev. Remus E. Wright, the family pastor. Former Vice President Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, may attend, and other political figures and celebrities are expected as well. A private burial will follow.

Both the memorials in Minneapolis and Houston will include personal tributes and eulogies about social justice, Sharpton said.

Due to the coronavirus, Fountain of Praise will be limited to 20% of its capacity and visitors will be required to wear masks.

Floyd’s final journey was designed with intention, Sharpton said. Having left Houston for Minneapolis in 2014 in search of a job and a new life, Floyd will retrace that path.

“They collectively said we need to make the first memorial statement from the city he chose to go to make a living, that ended his life,” he said.

Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, said that “for a person who was pretty much unknown to the world until just last week, this is unprecedented.”

“This has touched a nerve,” Carson said. “It’s been building up for all of American history. I think that people who are aware of the history of this country understand that there’s a lot to atone for and a lot to celebrate in terms of people who stood up for justice.”

The size of Floyd’s memorial reflects his impact and the need to recognize the widespread grief his death has caused, said Tashel Bordere, an expert on grief and assistant professor at the University of Missouri. It also reflects a tradition particularly in African American communities that large funerals can provide the recognition that a lost loved one struggled to receive in life.

But, she added, “grief goes far beyond the funeral; healing goes far beyond the funeral. Justice is experienced when people feel safe in their communities and in their lives.”

Carson said the impact of Floyd’s death would ultimately be measured by changes in how police treat African Americans and the disparate rates at which black men are incarcerated.

“Otherwise, it’ll just be the next George Floyd and the one after that,” he said.