(Maggie Stout/TommieMedia)

In each class I attend, a few classmates have a Yeti or Thermos filled with coffee. Whether it is 8 o’clock in the morning or late in the afternoon, students are sipping on caffeine-heavy drinks.

Coffee, energy drinks, tea, soda—many college students rely on these types of beverages to get through the day. Yet, the need for them often overshadows the potential harmful qualities they possess, particularly their caffeine output.

To understand caffeine’s effects, we need the scientific background first.

Caffeine is one of the most commonly consumed drugs. Yes, you read that right. It is technically a drug, which is defined as a medicine or other substance that has a physiological effect when ingested.

Its stimulating qualities provide users with an energy boost, something that college students typically need. It is absorbed into the bloodstream through the small intestines, and since it is water- and fat-soluble, it can pass through the blood-brain barrier. It has a direct path to the brain.

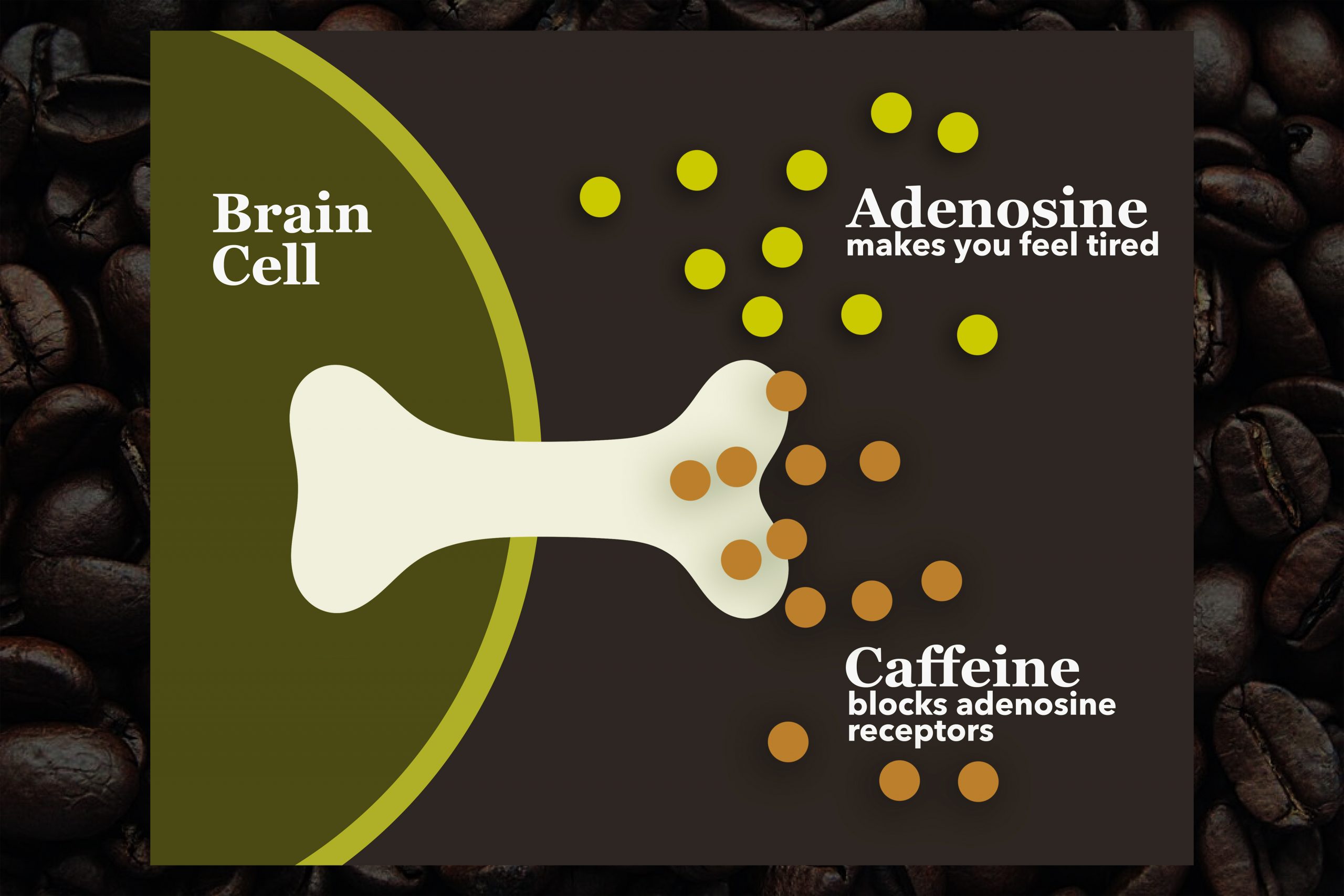

Caffeine’s chemical structure is similar to adenosine, a neurotransmitter in the brain that collects in specific receptors throughout the day. This buildup produces a “tired” feeling, signaling the need for rest or sleep. Since caffeine’s structure is similar, it can block these receptors, prohibiting adenosine buildup.

(Maggie Stout/TommieMedia)

Tolerance occurs when the brain starts producing more adenosine receptors. The added receptors allow for adenosine to signal, regardless of a person’s caffeine intake. However, people often increase the amount of caffeine they consume to achieve the energy boost they need and want.

Sorry, I’m a bit of a chemistry nerd, but understanding the chemical and biological basis for caffeine explains why so many consume so much.

It is hard to picture caffeine as addictive. It is not presented as nor thought of as a drug, and the sheer quantity consumed deters people from seeing it as a drug. Yet, over 90% of Americans consume caffeine in a day, coffee being the leading provider. It quickly becomes ingrained in morning routines and potentially necessary for a person’s daily functioning.

It is important to consider, though, that the consumption of caffeine can quickly begin doing more harm than good.

People may end up with an abnormal sleep pattern. As I mentioned earlier, caffeine blocks the brain’s natural way of determining tiredness. This disrupts the body’s daily cycle and a person’s brain is no longer in tune with their natural sleep requirements.

This disrupted rhythm can quickly become a vicious cycle. As we lose sleep, whether caused by caffeine consumption or not, we rely on caffeine more. Consuming more strengthens the habit and need for caffeine, thus ensuring the cycle continues.

On top of this, mental and emotional health can be weakened. Caffeine use may increase anxiety, irritability and other mood fluctuations—all of which are elevated during withdrawal. Just as it takes time to adjust to a regular caffeine intake, it takes time to adjust to being without it.

Granted, most college students aren’t addicted to caffeine. Does a cup of coffee help them get to class and be attentive while there? Probably, and that’s OK. However, students should be more conscious of the amount of caffeine they are consuming.

In all fairness, I like coffee. I usually drink it black, maybe a splash of milk or creamer, but as much as I enjoy it, my body cannot handle it. Even drinking it on a semi-regular basis is not enough for my body to gain tolerance. Coffee, and other caffeinated drinks, cause me headaches. So along with restlessness, my head hurts.

Now, I know I should stop drinking coffee or turn to a decaf option. But coffee on a Saturday morning? It’s tradition.

Yet, my caffeine intake is limited to coffee. I am picky about the teas I buy, and I hardly drink soda anymore. My body doesn’t function as well with caffeine as others’ do.

It’s up to each individual to determine how caffeine is a healthy amount for them. Doing so may require reevaluating other habits in our lives, which might just take a little energy boost to get through.

Maddie Peters can be reached at pete9542@stthomas.edu.