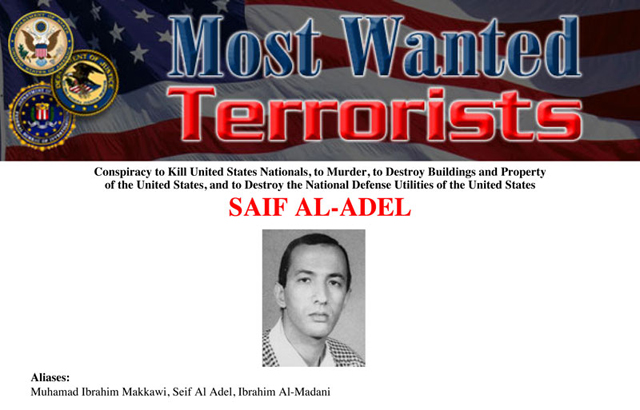

LONDON — The FBI’s most-wanted list shows a dated black-and-white photograph for the man wanted in connection with the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Tanzania and Kenya. Saif al-Adel, reads the glaring red banner, alias Muhammad Ibrahim Makkawi.

There’s only one problem: Intelligence officials and people who say they know al-Adel and Makkawi tell The Associated Press that they are two different men.

After Osama bin Laden’s death, AP reporters around the globe began hunting for fresh details on al-Adel — al-Qaida’s so-called third man because of his strategic military experience. Traversing a reporting trail that spanned from Europe to Egypt and from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran, a different picture started to emerge about al-Adel: that the FBI might have been working off a flawed profile of him that merged his identity with another person.

Intelligence officials from five countries and a few sources who say they knew the men personally over the years confirmed to the AP that al-Adel and Makkawi were two distinct people. Some of those sources came forward with two photographs that show two different men.

“That is certainly not Makkawi,” Montasser el-Zayat, a lawyer who represented Makkawi in Egypt, told the AP after looking at the FBI’s photo of al-Adel.

In response to several questions, the FBI declined to comment on whether al-Adel and Makkawi could be two different people or whether the information they had been using possibly was bad or dated, saying only that al-Adel, like others on the list, had been indicted by a U.S. grand jury. But the original documents in al-Adel’s case remain sealed, making it all but impossible for the public to see where the FBI got its original evidence or the basic details about al-Adel’s identity.

“The FBI will not disclose investigative steps, relevant intelligence, nor case details during an active investigation,” said FBI spokeswoman Kathleen R. Wright. “This policy preserves the integrity of the investigation and the privacy of individuals involved in the investigation. Investigators and prosecutors routinely review information and intelligence involved in each case.”

The nature of intelligence

The apparent error describing the man believed to be a top al-Qaida military strategist and bin Laden insider highlights the patchy or false intelligence that often goes into profiles of top suspects by the world’s intelligence services.

Many of the profiles are based on information obtained from captives under duress or worse. Some bits come from unreliable sources. Other tips are never verified.

On the surface, some may ask why the world should care; one man is a jihadist with a $5 million bounty on his head, the other a former jihadist turned al-Qaida critic. But the case raises important questions about the accuracy of FBI profiles and how stale or misleading intelligence could hamper searches.

Al-Adel’s profile, for example, was posted in October 2001 when the FBI “Most Wanted Terrorist” list was created — just a month after the Sept. 11 terror attacks. Although some of the descriptive details may be old, the FBI says the details are still accurate and relevant.

“We have no information there have been any significant errors regarding the individuals in which we are seeking the public’s assistance in locating,” the FBI said.

Yet since 9/11, dozens of people have been wrongly mistaken for suspected terrorists because of faulty or spotty intelligence.

A German man snatched by the CIA in Macedonia and tortured at a secret prison in Afghanistan is suing Macedonia for his ordeal after U.S. courts rejected his case on the grounds that it could reveal government secrets. The man says he was kidnapped from Macedonia in 2003, apparently mistaken for a terror suspect.

A Canadian engineer also caught up in the U.S. government’s secret transfer of terror suspects to ghost sites was deported to Syria when he was mistaken for a terrorist as he changed planes in New York on his way home. The Supreme Court refused to hear his case against top Bush administration officials.

“You are going to have good intelligence and bad intelligence, but the problem is when that bad intelligence is used to charge and detain people or to build cases against others,” said Ben Wizner, the attorney for Khaled el-Masri, the German who was sent to a secret prison and, according to Wizer, has suffered because of the trauma. “This faulty intelligence and disregard for the legal process has damaged and disrupted the lives of innocent people.”

Real Makkawi stands up

It is unclear exactly how Makkawi’s life has been affected. The former Egyptian army officer who worked in a counterterrorism unit has yet to come forward and did not respond to several emails sent by the AP.

Still, in May a man who identified himself as Makkawi sent emails to journalists and commentators, saying he had been mistaken for al-Adel. In one email to the pan-Arab newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat, which publishes an English edition in London, he claimed he was a colonel in the Egyptian army, has long been an opponent of al-Qaida and other jihadist groups and has been mistaken for al-Adel ever since settling down in Pakistan.

He says he and his family have been branded enemies of both the United States and al-Qaida — an unenviable position.

In an earlier message to the newspaper in July 2010, the same man criticized al-Qaida and Pakistan: “There is an immoral extortion campaign against the U.S. and its allies and the Islamic movement being led by Pakistan, for its own motives. Pakistan has all of these international terrorists in its hands.”

Pakistani authorities have said they have no knowledge of Makkawi’s whereabouts.