The morning of Sept. 15 began like any other day in late summer. Students at St. Thomas milled around campus, enjoying the warm weather between classes. It was Tuesday on the first full week of classes, and students and faculty alike were only beginning to find their rhythms.

While the morning began as any other, it did not end that way for five St. Thomas community members.

At approximately 9:48 a.m., philosophy professor Stephen Laumakis suffered cardiac arrest and lost consciousness while walking to teach a class in Brady Educational Center.

Laumakis doesn’t remember the events leading up to when he fell down on the sidewalk a few dozen feet from Anderson Student Center, nor does he have any recollection of what happened afterward, when he was given life-saving emergency medical care and rushed to the hospital.

Laumakis is fortunate that four Tommies – a professor, a lab manager and two students – were in the right place to lend critical aid to a stranger in need.

“He would be dead right now if it had not been for them moving so quickly,” said Mary Thomas, Laumakis’ wife. “We can never thank them enough for stepping up.”

The Professor: Amelia McNamara

After spending her morning prepping for a long day, her first on campus since the spring, Amelia McNamara, an assistant professor in the Computer and Information Science department, left her office in O’Shaughnessy Science Hall a few minutes early to prepare for her statistics class in ASC.

“I knew it was going to be stressful, but I was not expecting a medical emergency,” McNamara said.

Before leaving the building, McNamara came across a group of students walking the wrong direction down a one-way hall. She reminded them of the new COVID-19 regulations, and they all took the long way to the exit.

McNamara crossed Summit Avenue, then Cretin Avenue and made her way up the sidewalk toward the south entrance of ASC. It was then that she noticed a man – middle-aged, wearing a snazzy Hawaiian shirt and crisp, forest green shorts – walking toward her on the sidewalk.

“He didn’t look great,” McNamara said.

The man, Laumakis, took off his face covering and, seconds later, collapsed face-down on the sidewalk, breaking his glasses.

“I was kind of in shock,” McNamara said. “I didn’t know what had happened to him; I honestly didn’t know if he was still alive. He was breathing, but it was really irregular.”

McNamara rushed toward the fallen professor and called 911.

The First Student: Paris Edwards

After an unexpectedly short statistics lab in OSS, Paris Edwards, a junior entrepreneurship major, was among those students reminded by McNamara to take the long way around the building to follow the one-way signs. Edwards was happy to be done with class early and had some free time before working her afternoon shift as a school bus driver.

Edwards didn’t see Laumakis fall just ahead of her, but she heard the thump as he hit the pavement, together with the snap of his glasses breaking.

At McNamara’s behest, Edwards called Public Safety. It was 9:49 a.m.

The Lab Manager: Taylor Lesmeister

As he crossed Summit Avenue on his way from Owens Science Hall to Murray-Herrick Campus Center to drop off some mail, Taylor Lesmeister, a lab manager in the chemistry department and a St. Thomas alumnus, saw a man lying prone. Close by, a woman was talking frantically on the phone.

Confused at first, Lesmeister walked up and helped Edwards after two bystanders had turned the man onto his side. Upon realizing that the man was unresponsive, Lesmeister ran a short distance up the sidewalk toward a nearby emergency station to alert Public Safety.

As Lesmeister rushed up the sidewalk, the 911 operator told McNamara that someone had to administer cardiopulmonary resuscitation, CPR.

McNamara knew that during emergency situations, it is important to direct specific people to specific tasks. If every bystander thought calling 911 or performing CPR could be anyone’s job, then the responsibility would diffuse among the group, leading to potentially deadly indecisiveness.

She also knew this was happening in the midst of a deadly pandemic, and that ordering someone to perform CPR could put their own health in jeopardy.

“I didn’t know who would be comfortable touching him or getting close to another person,” McNamara recalled. “I asked, ‘Is anyone here willing to do chest compressions?’”

Edwards, who had taken a CPR certification class as a young teenager, didn’t consider her own safety before volunteering. She helped turn the professor from his side onto his back and knelt beside him to begin chest compressions.

“I wasn’t feeling anything,” Edwards said. “Everyone around me kind of just disappeared, and I was just worried about him.”

The Second Student: Bailey Keffer

Senior biochemistry major Bailey Keffer was on his way to his biology class in OWS. As he rounded the east side of ASC, Keffer saw Lesmeister activating the emergency station button. The two men knew each other; Lesmeister was Keffer’s lab manager and co-worker. Keffer approached Lesmeister, who quickly filled him in on the situation while they rushed back toward Laumakis.

Just six months earlier, Keffer had been certified as a trained emergency medical technician. He had been hoping to find a job as an EMT over the summer, but the pandemic waylaid his efforts. He hadn’t expected he would need to use his training until he was working in the medical field.

The training kicked in once he and Lesmeister reached the fallen professor.

“When I got there I just kind of knew that this is probably a heart attack. And then I saw erratic breathing as well,” Keffer said. “So I had heard of this stuff before, but I had never seen anything like this.”

Edwards was still performing CPR as Keffer checked Laumakis’ vitals and responsiveness.

Searching for a pulse, Keffer found none. He checked longer than he normally would because, he said, he hoped this wasn’t a worse-case scenario.

“You don’t want the situation to be the extremely serious one that it ended up being,” Keffer said. “Maybe he just fainted. He hit his head on the ground and he’s unconscious, because that’s a lot more easily manageable one from a medical standpoint.”

The Rescue

McNamara was still on the phone with the 911 operator, who was giving directions. McNamara told the operator every time Laumakis took a ragged breath. She pointed to Lesmeister and asked him to find an automated external defibrillator.

Lesmeister sprinted from the scene to grab an AED out of ASC, a few dozen feet away.

In ASC, Lesmeister ran up to two students working behind the desk at Tommie Central and asked them where to find the nearest AED.

A moment passed, the two students turned to each other and shrugged. They didn’t know.

Lesmeister realized he didn’t have time for the Tommie Central employees to look for the building’s emergency manual.

“Luckily, I have to follow a lot of safety protocols and stuff in the lab,” Lesmeister said. “So I figured all I had to do is find the fire extinguisher, and I knew that there would probably be one (AED) right next to it.”

He checked around the corner and saw the red, square medical unit attached to the wall.

Outside, St. Thomas Public Safety had arrived. The seconds ticked by in agonizing indifference. Edwards’ sole job was performing CPR, and she continued to do so. It was 9:53 a.m.

When Lesmeister returned with the AED, he and Keffer unbuttoned Laumakis’ shirt to attach the device’s electrode pads and waited as it analyzed its patient.

“Pretty much immediately, it registered that he didn’t have a heartbeat,” Lesmeister said.

Keffer directed everyone to stay clear as he pressed the button to shock Laumakis with the defibrillator to restart his heart rhythm. It was 9:56 a.m.

“It shocked the one time and then it gave a rhythm to do the chest compressions after that,” Keffer said.

Minutes passed. Edwards continued to perform chest compressions according to the AED’s automated direction.

“We kind of just went back to doing whatever we could to keep him alive until the paramedics showed up,” Lesmeister said.

Two minutes after delivering the shock, the AED registered signs of life. Laumakis was breathing, and his heart was beating steadily.

Less than a minute later, at 9:59 a.m. – about 10 minutes after Laumakis had fallen on the sidewalk – the St. Paul Fire Department medical unit arrived.

The medics then took over, shifting Laumakis onto a stretcher and moving him to the waiting ambulance. It was 10:02 a.m.

Afterward

As Keffer watched the professionals work, he turned to Lesmeister and said what he was thinking: “I’m actually late for class right now.”

Keffer made his way to his biology lecture and attempted to pay attention with little luck.

“Maybe it was just trying to get back into the normalcy of things,” Keffer recalled later. “Looking back at that lecture now, I barely remember anything from it. (My) heart was still kind of racing, constantly thinking about the situation.”

Lesmeister likewise realized that his services were no longer needed. “It was pretty stressful, so I kind of had to take a step back and take a breath,” he said.

Soon after, he left the scene to resume his trek to the on-campus mailroom.

Meanwhile, McNamara wrapped up her call with the 911 operator and checked in with a nearby Public Safety officer. Her help was no longer needed, and she realized that she was late to class as well. McNamara was still shaken by what happened, and since it was her first day teaching her statistics class in person, she couldn’t remember what room it was in.

“All I remembered was it’s on the third floor. So I got upstairs, and I’m peeking into rooms,” McNamara recalled. “And I don’t know many of my students, I know a couple of them and then they’re all wearing masks. So I’m walking through, then I was like, ‘Is this my class?’”

Luckily for her, it was.

“I talked with all my colleagues later, and they were like, ‘You could have just canceled class.’

But I didn’t think of that,” McNamara said.

Edwards was the only one of the heroic team with no pressing commitments, so she stayed a while to watch over Laumakis.

Meanwhile, Vice President for Student Affairs Karen Lange saw the ambulance from her third-floor office window in ASC.

“I had just finished a meeting, and I heard the ambulance,” Lange said. “I knew something was going on, but I wasn’t quite sure what was going on.”

Lange went down to the scene and found that the Public Safety officers had cordoned off the area and Laumakis was being treated in the ambulance. When she thanked the officers for their work, “They said, ‘Don’t thank us, thank her,’ and they pointed to (Edwards),” Lange said.

Lange approached Edwards, who told her about what had happened.

“She was incredible,” Lange said. “She was so calm and stayed calm throughout it. … She was very worried, obviously, about (Laumakis), and I was just so impressed at what she had done and what the other students had done.”

At the time, Lange did not know the man who had collapsed was Laumakis. She inquired afterward with her colleagues in Academic Affairs in an effort to identify him.

Laumakis was checked in to Regions Hospital at 10:16 a.m., 25 minutes after he collapsed. He was admitted as a “John Doe,” said his wife Mary Thomas.

Thomas said her husband usually brings only the materials he needs for class; his only form of identification was his St. Thomas ID.

“For some reason, that wasn’t enough for Regions Hospital to locate me,” Thomas said, or to identify Laumakis by name when he was admitted.

Thomas didn’t know anything was amiss until around 1 p.m., when Laumakis’ co-worker called to let Thomas know her husband had not attended class. The hospital called a few minutes later to inform her of his condition.

“It’s a good thing that Regions did catch us very soon after that call because I was in a panic,” Thomas said. “I thought maybe he had a car accident on the way down the school or something like that.”

The Hospital

Cardiac arrests, which occur when the heart stops beating suddenly and without warning, are extremely deadly. When victims are stricken outside of the hospital, survivability rates average in the low double-digits, according to a report from the American Heart Association and National Institutes of Health.

According to Thomas, Laumakis was placed in a medically-induced “therapeutic hypothermia,” which is when the body temperature is lowered to between 89 and 93 degrees Fahrenheit. The treatment is designed to reduce the risk of brain damage following a cardiac arrest and subsequent coma, according to the American Heart Association. He was in a coma for six days.

“It’s meant to slow everything down and give the body a chance to heal,” Thomas said.

And heal it did. Laumakis’ cardiac health is now back to normal, according to Thomas. He woke up on Sunday, Sept. 20, to the great relief of his wife and two college-age daughters. Ever the philosopher, Laumakis, who has taught at St. Thomas since 1990 and was the longtime director of the Aquinas Scholars Program, had plenty to say.

“He did a lot of mumbling about the Buddha’s teaching and how life is impermanent,” Thomas said. “We got a lot of Buddhism in the first few days. So now he has switched over. He’s back on some of his medieval philosophy.

“We’re getting a lot of St. Thomas Aquinas…”

Thomas stressed how lucky Laumakis was to have woken up at all and she was grateful the incident didn’t happen on one of her husband’s daily, solo hour-and-a-half walks.

“If he had been on one of these walks, he wouldn’t be here today,” Thomas said.

Even so, she added, “I wish it had been the one day where he decided to … go across the lawn rather than going on the sidewalk.”

When Laumakis collapsed, his head hit the sidewalk. Now that the cardiac treatment is behind him, the biggest concern is the effects of his concussion.

Laumakis was sent home on Oct. 2, 17 days after his cardiac arrest.

In his recovery, Laumakis has weeks of therapy ahead; he is immensely grateful to the rescuers, who were all strangers to him until the morning of Sept. 15.

“Hell, for all I know I could still be lying there waiting for help if my guardian angels were not in the immediate neighborhood!” Laumakis said.

Edwards, Keffer and Lesmeister

The two students and lab manager agreed that they learned a lot while handling the situation and its aftermath.

When Lesmeister first came upon the scene, “there wasn’t hardly anyone else around yet,” Lesmeister said. “There were other people walking by but there wasn’t like a big gathering of people or anything.”

Lesmeister added, “Thinking back on it, I really have learned that not many people are willing to jump into action right away.”

Keffer remembers the intensity of the situation and how he had no choice but to think fast.

“You’re so overwhelmed with everything that’s going on that you forget a lot of smaller things,” Keffer said. “Immediately after even, I was like, Oh, I could have done that better.”

For Edwards, the events of the dramatic morning have continued to play out in her head.

“I did have to walk by it once and it kind of just flashed in my memory, just everything all at once,” Edwards said. “It’s a little overwhelming.”

Edwards, Keffer and Lesmeister each were awarded a Merit Pin by the Public Safety staff. It marks the first time since the school’s founding in 1885 that anyone outside the Public Safety department has been awarded the pin.

“It is clear they performed lifesaving procedures that ultimately saved a life. They embodied the University of St. Thomas mission statement,” Public Safety St. Paul Campus Manager Zachary DuBois said.

And embody the common good they did.

“This is what our community is about,” Lange said, “We care for each other.”

Editor’s note: According to our investigation, there were other bystanders who helped Edwards, McNamara, Lesmeister and Keffer by helping roll Laumakis over and position his body for CPR. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine the identity of these individuals.

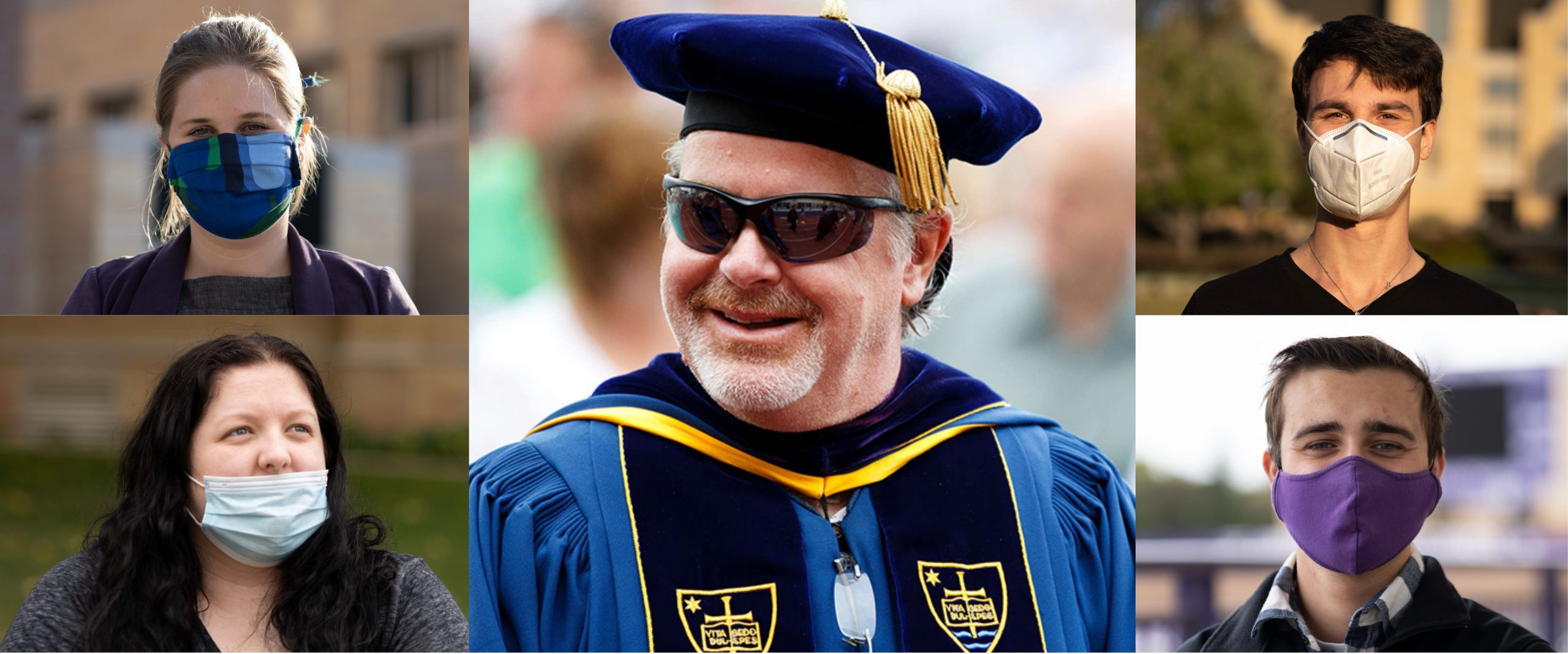

The photo of Laumakis was supplied by his family, and the photo of the Merit Pin was courtesy of Lesmeister. All other photos were supplied by TommieMedia’s Chief Photo Editor, Song Johansen.

Sawyer Rutan can be reached at sawyer.rutan@stthomas.edu.

Burke Spizale can be reached at spiz8477@stthomas.edu.

Justin Amaker can be reached at justin.amaker@stthomas.edu.

Thanks to all who helped this fallen philosopher! You are all my guardian angels! Thank you, thank you, thank you! Dr. L

As the mother of a current Tommie and a survivor of cardiac arrest, I love this story! Let’s just make sure we use it as a teaching moment: great idea to make sure student employees and other staff know where fire extinguishers and AEDS are. . .and how to use them!!

Words are hardly sufficient to express our gratitude to the heroes who saved the life of our friend and colleague Steve Laumakis. We will never forget how St. Thomas students, faculty, and staff–Bailey, Taylor, Amelia, and Paris–sprang into action when many of us might have been paralyzed by fear or indecision. And thanks also to Tommie Media for this well-reported story!

Wow these guys are all heroes!