Gas prices in Minnesota are lower than they have been in years because of a combination of supply and demand factors.

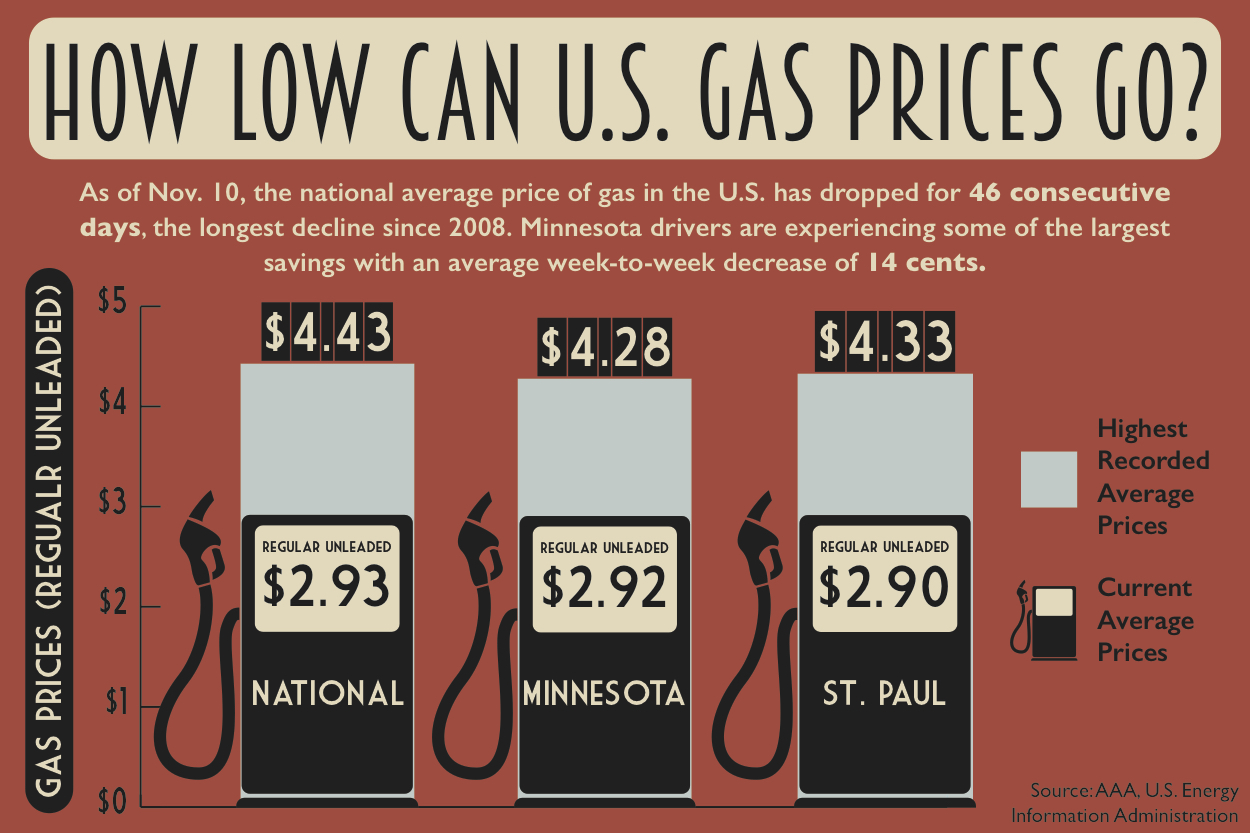

The current average is hovering around $2.90 – as opposed to around $3.20 a year ago – according to the Daily Fuel Gauge Report. Economics professor Rob Riley said the drop in prices is a result of a decrease in global demand and an increase in production of oil.

“It’s pretty clear that the U.S. has cranked up the production of both oil and natural gas,” Riley said. He added that other countries have increased oil production, as well.

The amount of oil and gas being consumed globally has also decreased partially due to economic slowdowns in Europe and China, Riley said.

“(China) had artificially boosted a lot of economic activity, like spending and buying through basically credit, bank credit, and that isn’t sustainable,” he said. “So banks in China are slowing down, which means consumers have less money to buy stuff, and the whole economy slows down.”

Riley said cuts in government spending in Europe also contributed to the slowdowns.

“What they call ‘austerity measures’ – where the government basically tightens its belt … That can adversely affect economic activity,” he said.

This combination of greater supply and less demand drives crude oil and gas prices down, a situation ideal for consumers.

For student commuters like senior Joe Janochoski, who lives off campus and drives to school, the change has been noticeable.

“It’s definitely been nice. It’s probably dropped the price about five bucks each time I buy gas,” Janochoski said.

When it comes to the future of gas prices, Riley said there are several factors at work.

“One would be what the OPEC nations do … if governments of countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, others, become really nervous about the drop in prices, they could agree to lower global production. They’ll cut back on supply and try to drive prices back up,” Riley said.

Riley said another factor would be an economic resurgence in Europe, as increased economic activity would re-boost demand for crude oil and gas. But even if either of these happen, the result would remain to be seen.

“The question is how far it would push supply of energy back down and demand back up,” Riley said.

Lauren Schaffran can be reached at scha7492@stthomas.edu.