The pause of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine was a positive precaution for the public.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration recommended that the vaccine’s distribution temporarily halt after six cases of severe blood clots were reported by women who had received the shot. Causality has not been proven, though.

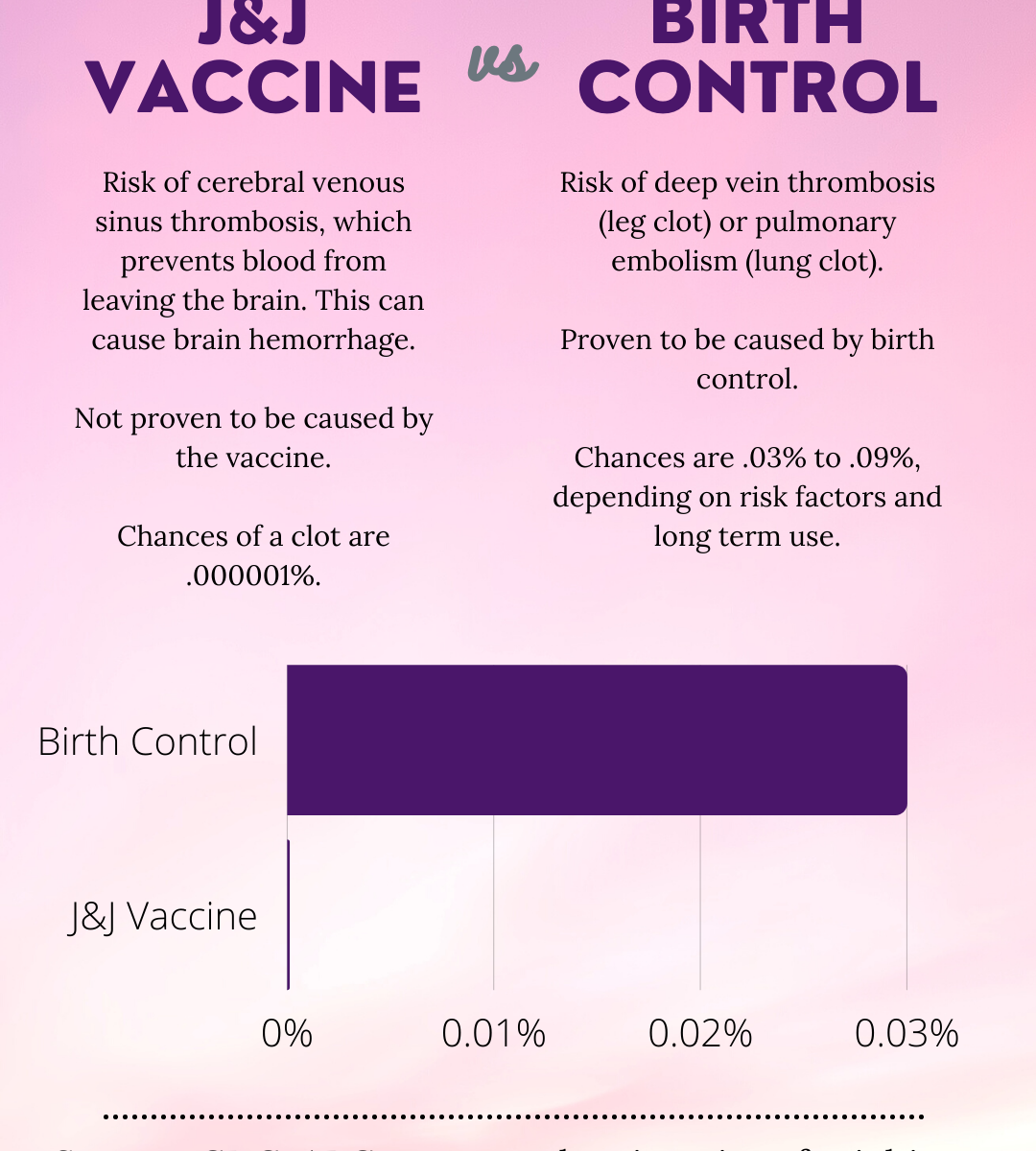

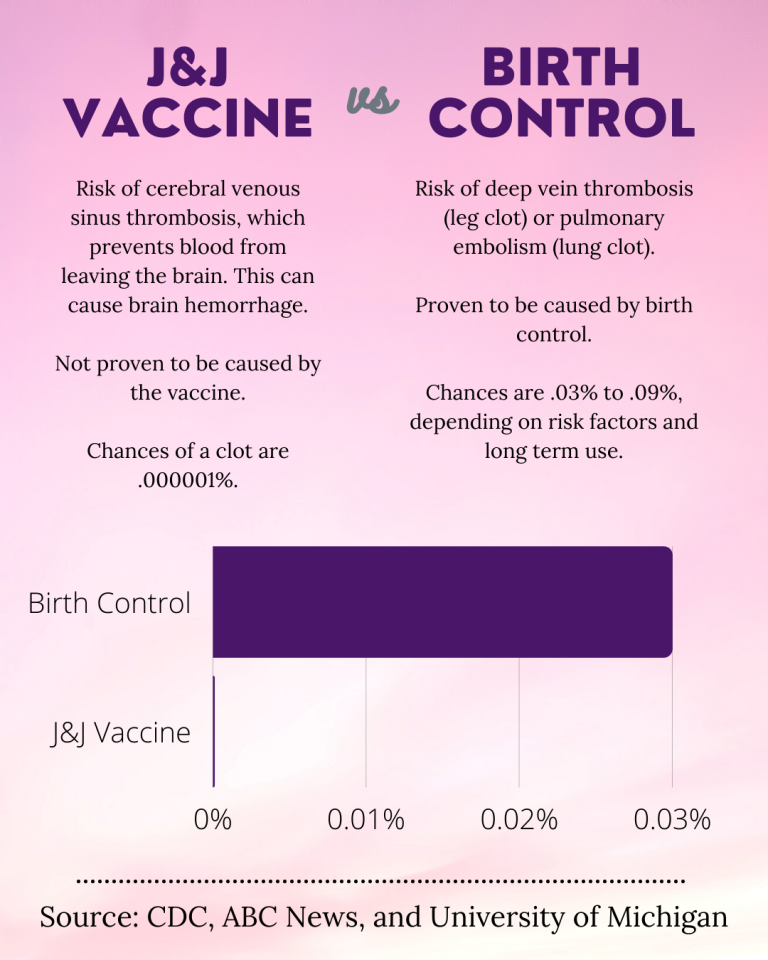

According to the CDC, over 6.8 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine had been administered in the United States as of April 12. Regarding the reported blood clot cases, the CDC said, “In these cases, a type of blood clot called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) was seen in combination with low levels of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia). All six cases occurred among women between the ages of 18 and 48, and symptoms occurred 6 to 13 days after vaccination.”

Though, on April 23, the recommendation was lifted. The J&J vaccine can be distributed once more, except with an added warning of potential blood clots.

A single digit number of cases out of millions seems like nothing. But vaccines are preventative safety measures. Any number of harmful outcomes would be too many.

It’s a matter of public health. Of course, the pause was necessary, at least to reevaluate the vaccine’s effectiveness or worthiness for use. Though, the vaccine’s pause started an interesting— and well-needed and overdue— conversation regarding women’s health.

Much of the discourse was centered on birth control. Combination hormonal birth control, typically referred to as “the pill,” is an oral contraceptive. Many people, though, take birth control to reduce period symptoms, treat acne or manage endometriosis, for example.

Different brands and types of pills do different things, at least in regard to the hormones they contain and their effect on the reproductive organs, but more or less, combination birth control contains various levels of estrogen and progesterone (hence the ‘combination’ in the name).

Birth control patches also deliver estrogen, and typically do so at a higher level than low-dose pills.

Some women are at risk of blood clots by taking the pill. Clots usually form as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT, in a leg) or a pulmonary embolism (PE, in a lung). They can occur together if a blood clot in the leg dislodges, travels through the body and catches in a lung, thus causing a PE.

Approximately one in 3,000 women per year who take combination birth control are at risk for developing a clot. Maybe this is a hard to figure to grasp, but in considering the J&J vaccine, distribution stopped because six out of 6.8 million recipients experienced life-threatening clots.

The shot hasn’t even been directly proven to be the cause of the clots, but it was stopped— for six people.

Higher amounts of estrogen in combination birth control pills is the recognized culprit for blood clots, so most pills now contain lower doses. In turn, the risk for blood clots has reduced.

Even so, the risk is there. No one seems particularly concerned in pausing the use of these drugs to protect people.

And for the number of women, people who menstruate and female-identifying people who do take an oral contraceptive, their health and safety should be top priority, too.

Combination birth control pills should be adjusted and constantly monitored. The risk of blood clots is far higher from oral contraceptives than the J&J vaccine. Obviously, the pause in the vaccine is a good thing— again, health and safety are the ultimate goal. But the quick halt in use for so few cases should be a glaring sign that certain birth control methods need to be made safer.

Yes, the vaccine is for the entire population and is saving lives. It is helping the country gain some ground on the pandemic. And no, most reasons for taking birth control are not life or death. That doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be any less safe.

Emergency health situations like a global pandemic deserve our time, effort, attention and resources. But so does routine women’s health.

Regardless of personal beliefs or opinions on oral contraceptives, or if an individual consumes them or not, they should be safe. Women who choose to use any form of combination birth control should feel safe doing so. Not only because that is what is expected, but because it’s an assurance that women deserve.

Maddie Peters can be reached at pete9542@stthomas.edu.