(Kayla Mayer/TommieMedia)

On January 26, 2020, a helicopter crash in the hills of southern California sent shockwaves around the globe. The first confirmed deaths: Kobe Bryant and his teenage daughter Gianna.

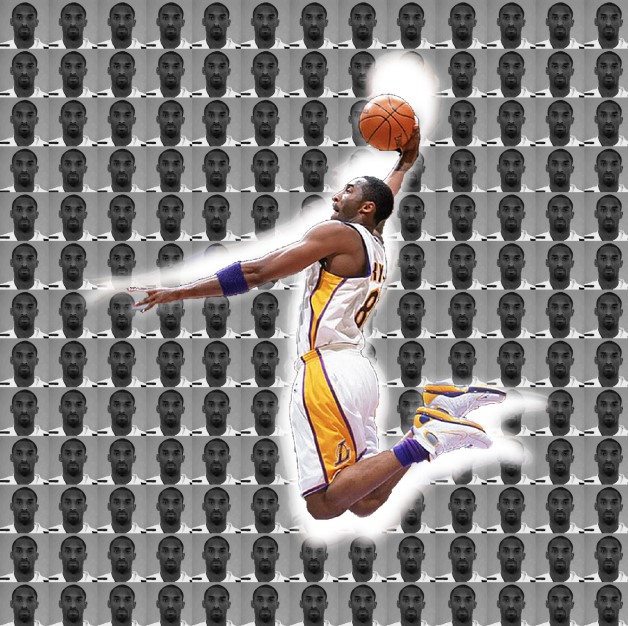

Bryant was a household name in basketball. Drafted by the Los Angeles Lakers in 1996, 18-year-old Bryant was the youngest player to play in an NBA game. He went on to have a dynamite career, retiring four years ago as the third-highest scorer of all-time until Lebron James overtook him in late January.

Bryant’s legacy extends beyond fans shouting “Kobe” before throwing paper balls into trash cans. As an Oscar-winner, mentor and women’s basketball ally, he worked to promote the game that changed his life.

And yet beneath the shiny veneer of idolizing obituaries lies a 2003 sexual assault charge.

All the accomplishments are important parts of who Bryant was, but these realities co-exist with a darker instance that humanizes him and knocks him off of the godly pedestal some fans had placed him on.

Bryant was human. Sure, he did a lot of good things, seemed to be a good father and a good husband, but he did some bad things, too.

He had sex with a woman who did not consent.

Bryant was formally charged for the assault, but before the trial started, the victim agreed to dismiss the case with a public apology from Bryant. In his apology, Bryant admitted that at the time, he had believed it was consensual but, looking back, realized it wasn’t.

The 2003 case started conversations that should have been had earlier. Consent wasn’t as widely acknowledged or taught as it is now—thanks to the work of the Me Too movement. It was cases like Bryant’s that helped bring the importance of consent to the spotlight.

Following the case, Bryant fell back on his Catholic faith, citing a conversation with a priest as a “turning point” for him. He continued to practice the faith up until the day he died, attending a Sunday mass that morning.

He made a mistake, acknowledged it and learned from it, but that doesn’t make up for the physical, emotional and psychological trauma that he caused the victim. He also doesn’t deserve to be condemned forever.

Bryant is an example of the complexity of human life. Sometimes, there is no black-and-white judgment to be made, and there is no purely good or purely evil person. Bryant’s life was riddled with a mix of good and bad things, just like the rest of us.

The confusion surrounding the best way to remember Bryant raises a significant question: How should we remember a celebrity who was well-respected but did something so harmful?

Many prominent figures have been accused of sexual assault or harassment recently. Where do these allegations belong in their future obituaries and memorials?

There is more at stake here than the reputations of the accused. To each and every one of these cases, there is a victim. Where do their stories fit in our remembrances? They, too, deserve respect, and even though they may not be prominent figures, they will also leave a legacy when they are gone.

The questions that Kobe Bryant’s conflicting legacy raises aren’t easy to answer. These cases and the people involved are complex, but the worst thing that we could do is fall into the trap of the single-sided story. We can’t project what we wish he was onto who he actually was.

Kobe Bryant was a legendary basketball player, father, husband, mentor and role model to young players, and he was accused of sexual assault. He was human, just like the rest of us.

Kayla Mayer can be reached at maye8518@stthomas.edu.