When My Chemical Romance broke up in 2013, my adolescent heart broke knowing that I would never have the chance to rock out to “Teenagers” in concert.

My hopes were dashed again in 2016 when the band’s account tweeted a video that led to talk of a reunion tour. The account later tweeted that it was merely a teaser for the anniversary of their album, “The Black Parade.”

Finally, on January 31, 2020, my moment had come. Following the success of a reunion concert in December 2019, the band announced their first U.S. tour in nine years.

I waited, phone in hand, as the minutes ticked down to noon and followed directions as fast as I could to buy tickets. However, I was immediately sent to an online queue, where I watched a tiny digital man mark my progress in line for 50 minutes. When Ticketmaster finally brought me to the purchase site, every seat that I tried to buy was already sold.

To top off my disappointment, the prices on resale sites had hit the thousands. I hate to put a price on the fulfillment of my emo dreams, but that’s much too high.

My little punk-rock heart was broken . . . again.

Still, my experience was a dream compared to others’. Some fans reported being kicked out of their spot while waiting online, forcing them to the end of the 2,000+ queue and decreasing their shot at buying a ticket.

The My Chemical Romance ticket fiasco is just one example of the monopoly that Ticketmaster holds over the ticketing industry.

Before the company merged with LiveNation in 2010, it controlled 80% of the ticket sales market, and today, the conglomerate owns over 200 venues and manages 500 major music artists.

Ticketmaster’s hold on the ticket market leaves no consequences for overcharging. The Justice Department is investigating whether LiveNation pressured venues to use Ticketmaster, therefore violating antitrust laws.

However, the bigger problem in the ticket sales industry is scalpers. Through sheer manpower and automated software, ticket resellers beat out individual buyers.

For in-demand concerts like My Chemical Romance, bots will reserve seats without purchasing, triggering the site to mark the seat as sold instead of available to actual buyers. Scalpers then prey on desperate fans and jack up the price of the resale ticket to make a profit.

CAPTCHA tests and ticket limits don’t stop the bots. Bots can bypass the blurry images and jumbled characters and work around ticket limits. Purchasing sites claim to cap the number of tickets a single customer can buy, but a large amount can still wind up in the hands of a limited few.

An example is when a single broker bought over a thousand tickets to a U2 show at Madison Square Garden. Plus, some limits only apply to single transactions, meaning a user could make multiple purchases of the max number of tickets.

In its 2018 report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office gave possible solutions to the scalping crisis, including making tickets as non transferable and capping prices on resales.

Ticketmaster has made efforts to crack down on reselling. Behind these efforts is the changing idea of what a “ticket” is. Instead of being the right of entrance to an event, Ticketmaster is grouping the buyer and ticket together more and more through its Safetix system.

However, Ticketmaster may not be as committed to ending the injustices of scalping as it would seem.

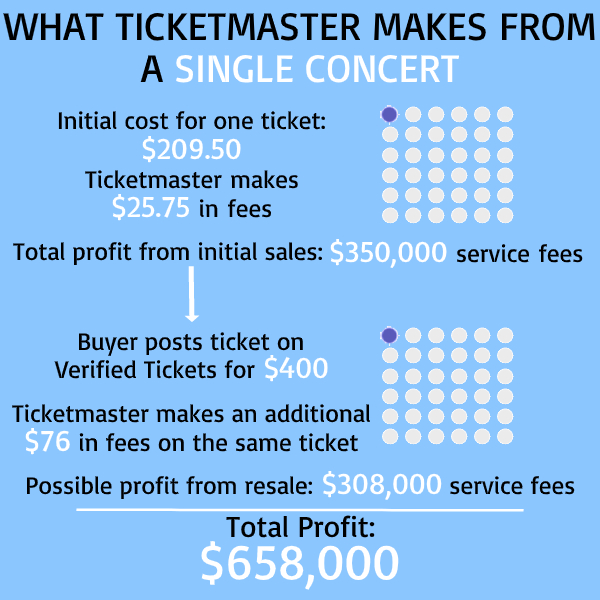

The company chose to create its own “secondary market” instead of partnering with pre-existing resale markets. This marketplace allows the company to sell first-round tickets at normal prices to ease suspicions, then go ahead and get another cut when some tickets are resold at higher prices on the Verified Tickets market.

Furthermore, Ticketmaster was accused of colluding with scalpers through a secret program called TradeDesk. When asked by one undercover journalist at a live entertainment conference, a Ticketmaster representative said that the company wouldn’t regulate the use of multiple accounts and even admitted to knowing someone with over 200 accounts.

The Canadian Broadcasting Company determined that by working with scalpers, Ticketmaster could make up to $658,000 in fees for a single concert, with half of the revenue coming from scalped tickets.

An end to scalping isn’t in sight. It’s legal, difficult to regulate and possibly even supported by the only company that has sway in ticket sales.

I just wanted to live out my best emo life in a decently priced stadium seat. If you need me, I’ll be hiding in a hoodie and listening to “I’m Not Okay (I Promise)” on repeat.

Kayla Mayer can be reached at maye8518@stthomas.edu.