As voters in Virginia grapple with photos of their elected officials dressed in blackface, the conversation on racist content in college yearbooks and newspapers is taking place at the national level.

The University of St. Thomas is about to enter that conversation, as students have unearthed photos of blackface in The Aquin Newspaper and Aquinas Yearbook online archives. TommieMedia confirmed at least three photos of blackface dated 1948, 1951 and 1979.

A photo from the 1948 Aquinas Yearbook shows students in blackface during a homecoming variety show.

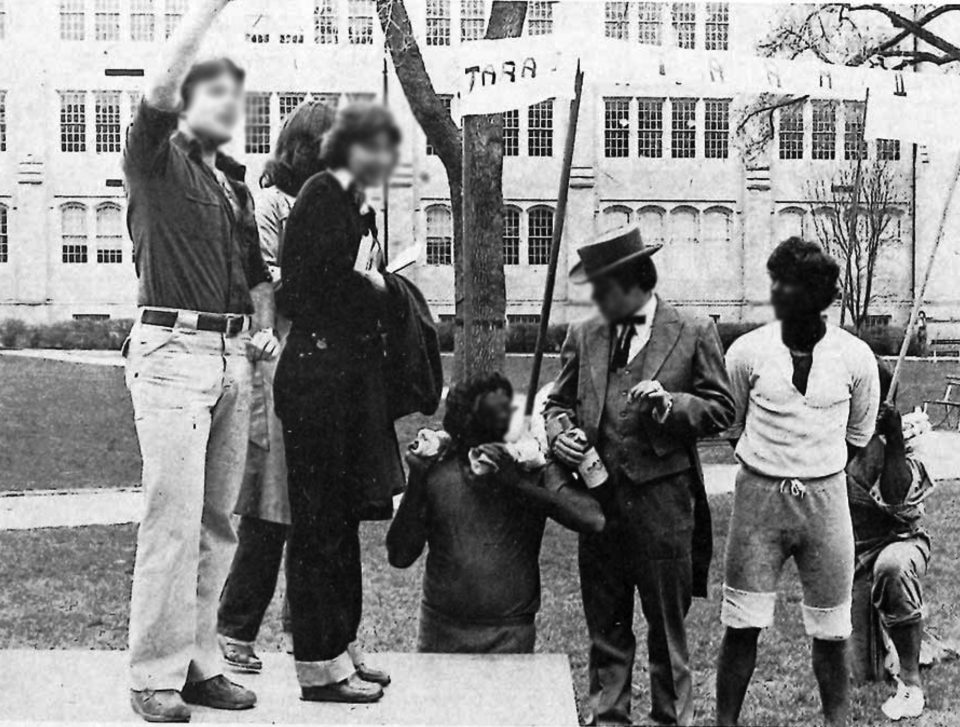

In 1979, the All College Council, a former version of the Undergraduate Student Government, sponsored a “Slave-Master” costume contest.

In 1980, a first-year student came back to his dorm room to find a racial slur and the phrase “go home” written on his door, just as first-year student Kevyn Perkins did last fall.

“We’re not the same place that we were in 1911,” said Yohuru Williams, historian and dean of St. Thomas’ College of Arts and Sciences. “We’re not the same place we were in 1986. We’re a different place today. We’re co-ed, we have students of color, we have African-American administrators, administrators of color. Do we have work to do? Do we have a lot of growing to do as an institution? Absolutely.

“But to say that we’re racist at our core, somehow we’re no different than we were in 1986? Not productive. It doesn’t force us to deal with those things that we can actually do to deepen the changes that have taken place and think about how we can be better.”

The 1948 and 1951 photos depict students in blackface while performing in homecoming variety shows. The 1951 yearbook caption describes the photo as a “Black face routine,” while the 1948 yearbook uses a racial slur referring to students “singing and hoofing.”

“We have to constantly battle sexism, racism, economic inequality in this country,” Williams said. “It is the constant struggle. To assume that righteous indignation about something that happened 30 years ago equates with progress, is not progress. To find a way to say never again, for anyone, is progress.”

Ann Kenne, head of special collections and university archivist, said she first came across the photos around a decade ago when the yearbooks and newspapers were being digitized for the online archives.

“Our job in the archives is to document the institution,” Kenne said. “Some of those insensitive things are a part of the university’s history. We don’t try to hide it, but… if we put something like that in a display, we would want to put some sort of explanatory material with it, talking about the context in which it was created. It wouldn’t be there for shock value, but it would be in the context of what was going on at the university, in the country at that time.”

Student discovery

A photo from the 1951 Aquinas Yearbook shows two students delivering “a Black face routine” during the homecoming “Tiger Show.”

Junior and USG Vice President of Administrative Affairs Jacob Fette found the photos a few weeks ago while looking through the online University Archives.

“I got curious, so I went and started looking around online,” Fette said. “It didn’t take me long just to type the keywords ‘black face’ in and find some stuff.”

After Fette sent junior Bizzy Stephenson screenshots of the photos, Stephenson decided to post them on her Instagram story.

“Not so friendly reminder that predominantly white institutions have not too distant histories of things we would like to imagine never happened at the place we live and learn,” Stephenson wrote in her post.

Stephenson said she posted the photos in an effort to get fellow students thinking about racism.

“My (St. Thomas) degree holds everything that has happened here, and that’s how I feel about the same hate crimes that are happening now,” Stephenson said. “My degree is tainted by the people who are committing hate crimes, but not only by them, but the people who are complicit in that too.”

Professor Debra Petersen teaches communication of race, class and gender at St. Thomas. A screenshot of Stephenson’s post was brought to her attention by a student.

“Especially at this time in St. Thomas history, when we’ve made a real commitment to dealing with racial issues… I know there are some people who are like, ‘the past is past,’ and I’m like, no,” Petersen said. “I think that’s really important that we go back and look at that, and I guess, not so much for blame or pointing fingers but to say that this was happening here too.”

Petersen covers racial issues such as negative stereotypes of African-Americans in her class.

“I think St. Thomas needs to do more with our history,” Petersen said. “I’ve been here since 1990 and I haven’t seen a lot of looking to the past.”

Student government-sponsored racism

In 1979, The Aquin newspaper published descriptions of a “Slave-Master” costume contest. According to the article, the contest was held during Mardi Gras week and prize money of $75 was awarded to the two students who dressed as the “most convincing master and slave.” $50 was awarded to second place and $25 to third.

“My god, that’s the building I teach in right behind it, isn’t it?” history professor David Williard said when he looked at the photo of students gathered for the contest in front of what appears to be Albertus Magnus Hall, now called John R. Roach Center for the Liberal Arts.

One student is dressed as a slave-master in a suit and tie, while two next to him are dressed as slaves in blackface and T-shirts.

“I have never seen a slave auction or slavery represented in blackface in a post-World War II context (or) in a post-Civil Rights context, and I think it’s shameful. I think St. Thomas should be appalled,” Williard said.

Williard said the St. Thomas contest differs from events that would have taken place at Southern universities, due in part to the context and history of slavery in the Confederate States compared with Union states such as Minnesota.

“(Southern) celebrations would be more gauged toward a particular valence of the memory of slavery that celebrated the positive aspects of Southern culture and less that harped on the institution itself,” Williard said.

The May 11, 1979, issue of The Aquin held multiple letters to the editor expressing outrage over the contest’s existence.

“Some of you may be under the illusion that slavery was a big joke or something to be proud of, but in reality, slavery was an extremely tragic and unfortunate incident in this country,” wrote one student associated with a minority students group. “To be sold away from your family and treated as if you were an animal is certainly not my idea of something to be taken lightly. Apparently, some of the people on this campus think quite differently. Also, I see absolutely no humor in white students painting themselves black and making a spectacle of themselves.”

The Aquin also published another student’s defense of the contest.

“I am not a racist, nor have I ever been accused of being one,” wrote the second student, a member of the All College Council. “I did by no means intend to degrade the Negro race, nor mean for them to take my behavior as an insult, any more than I would take the portrayal of a farmer (my father’s profession) or an Irish immigrant (my ancestral background) as an insult.”

A third student, a leader of the All College Council, wrote a Letter to the Editor to apologize for the event.

“The ACC and I wish to apologize for ‘that contest,’” the third student wrote. “It should have never taken place and will never take place again. It not only was an unkind and racist show of immaturity, it was also in poor taste. Excuses are insufficient reparation. However, we hope the students will come to realize this was an event sponsored out of ignorance and possibly naivete rather than malice.”

A photo from the May 11, 1979, issue of The Aquin shows students gathered for the “Slave-Master” costume contest on campus. This photo has been edited to obscure the identities of students pictured.

The same hate crime, 39 years ago

Last semester, first-year student Kevyn Perkins returned to his dorm room to find a racial slur and the phrase “go back” written on his door in Brady Hall. In 1980, Ron Jones found the same slur and the phrase “go home” written on his dorm room door in Ireland Hall.

“It’s literally the exact same, but it took place over 40 years ago,” Jacob Fette said. “It’s like, as much as things have changed, in some ways they haven’t. They’re still the same.”

While the specific hate crime may have been the same, Dean Williams pointed out that the university has made significant progress toward racial equality since 1980.

“There wouldn’t have been a black dean here 30 years ago,” Williams said. “There also wouldn’t have been female leadership 50 years ago. You can’t say we haven’t made progress.”

An article in the Feb. 22, 1980, issue of The Aquin by Julie Kramer presented perspectives from students of color on campus racism.

“‘If I had known I had to go through these experiences, I wouldn’t have set foot,’” a student of color said in The Aquin article.

Williams stressed that change does not occur without resistance and struggle.

“It’s horrible that we live in a society where cowards think that it’s justified to scrawl racist graffiti on people’s doors,” Williams said. “If we walk away, if you leave the school and say, I give up, that’s not going to produce change.”

What now?

Bizzy Stephenson believes students are responsible for acknowledging their school’s history and changing the culture themselves.

“I think it’s so easy to say, ‘administration’s not doing their job, they should do something.’ I’m much more interested in students, and to clarify, white students, taking individual responsibility for their own learning and exploration,” Stephenson said.

Fette hopes the administration holds a teach-in or event about St. Thomas’ racial history.

“I don’t know if the student government necessarily has a role in this,” Fette said.

Fette and Spencer brought their findings to a university administrator.

“(The administrator) wanted to talk to a few other co-workers before we move forward with anything,” Fette said.

Fette said in the future, all students will be required to go through mandatory online diversity training similar to the sexual assault and binge-drinking courses first-year students must take.

“It’s part of President (Julie) Sullivan’s action plan to combat racism, so right now the university is in the process of selecting a vendor, and we have focus groups from student government who are testing out the different vendors, seeing which one is more appropriate or which one would be best for UST,” Fette said.

Williard believes the best answer for St. Thomas is a historical education that treats racial issues with care and intellectual rigor.

“I don’t think a slapped-together workshop in a week’s time conveys to students that we’re serious about this,” Williard said. “I think it conveys to students that we’re serious about our image.”

Williard cited Georgetown University’s handling of the discovery that the school had owned and sold slaves as a good model to address past institutional racism. Georgetown has apologized, re-named buildings on campus to commemorate sold slaves and offered preferential admissions to the descendants of slaves.

“St. Thomas, obviously, is an institution that never had financial ties to slavery, at least not direct ones,” Williard said. “But if it has ties to these practices, it might think about what it can do in communities locally and regionally that would have been excluded… from full belonging at a ‘inclusive institution.’ ”

According to Williard, community engagement and concrete action is paramount to long-lasting change.

“We can brand ourselves, we can embrace a mission statement, but if that extends only to paper, if that extends only to words, then our institutional footprint is this: Our institutional footprint is that people three to four miles down the road in the Rondo community or in North Minneapolis see us as a white university,” Williard said. “I think to undo that work means going far beyond buttons and slogans and hashtags.”

TommieMedia has decided not to publish names or identifiable faces of students involved in the photos or events described in this story. We wrote this story hoping to create dialogue about racism, equality and discrimination on our campus; we do not seek to demonize individuals for actions that took place 40 years ago or more. Full editions of The Aquin and the Aquinas Yearbook are available online.

Solveig Rennan can be reached at renn6664@stthomas.edu

Well reported, valuable information, and incredibly relevant to talking about history and racism in context. Makes me proud to be an alumni, seeing the newspaper take charge on the distribution of this information. I admit I dislike having the perpetrators unnamed, but as long as the original pages of the yearbook in question remain unedited I suppose it’s a decent idea to protect the university from defamation suits.

This is an excellent piece of journalism, of which you should be proud. Well-researched and well-developed article about how the history of our university fits into a national discussion of critical issues of racism and white supremacy. I particularly appreciate the responses of our students, faculty colleagues, and dean as we all consider what our individual role is in shaping institutions of which we are a part.

Thank you for this important historical research. We can’t know where we are if we don’t acknowledge where we came from.