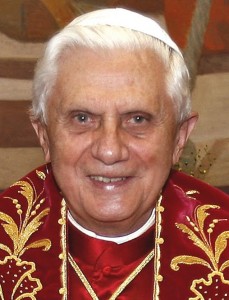

ZAGREB, Croatia — Pope Benedict XVI strongly backed Croatia’s bid to join the European Union as he arrived in the Balkan nation Saturday, but said he could understand fears among euroskeptics of the EU’s “overly strong” centralized bureaucracy.

The pontiff also expressed the Vatican’s long-running concern that Europe needs to be reminded of its Christian roots “for the sake of historical truth” as he began his first trip as pope to Croatia, a deeply Roman Catholic country that his predecessor visited three times during and after the bloody Balkan wars of the 1990s.

Benedict is spending the weekend to mark the Croatian church’s national family day, and he was warmly welcomed by thousands of young Croats who braved a steady rain while waiting for Benedict to arrive for an evening prayer vigil.

“We will stay here all night if we have to!” said Josipa Petrocic as she stood in Zagreb’s main square amid a sea of Croats wearing plastic ponchos and singing and dancing. “We do not mind the rain, we would stay even if it snows because we love the pope.”

Benedict’s visit is a boost to the conservative government’s efforts to finalize EU accession negotiations. Croatia is expected to learn this month or next if negotiations to join the 27-member EU bloc can be concluded, with membership expected in 2012 or 2013. The yearslong process has soured many Croatians on the EU, as has the recent sentence handed down by the Hague tribunal against a Croatian general convicted of war crimes but considered a hero at home.

Benedict sought to encourage Croatia’s EU bid, saying it was “logical, just and necessary” that Croatia join the EU given its history and culture is so strongly rooted in that of Europe.

“From its earliest days, your nation has formed part of Europe, and has contributed in its unique way to the spiritual and moral values that for centuries have shaped the daily lives and the personal and national identity of Europe’s sons and daughters,” Benedict said upon arrival at Zagreb’s airport.

But he acknowledged in comments to reporters aboard the papal plane that a certain fear or skepticism of joining the EU is understandable given Croatia’s small size and different values than those of other, more secularized EU nations.

“One can understand there is perhaps a fear of an overly strong centralized bureaucracy and a rationalistic culture that doesn’t sufficiently take into account the history — the richness of history and the richness of the diverse history” that Croatia offers, he said.

He urged Croatia to make as its EU mission “promoting the fundamental moral values that underpin social living and the identity of the old continent.”

Croatian President Ivo Josipovic, who greeted Benedict at the airport, concurred, saying Europe wouldn’t be unified were it not for the deeply Christian values of forgiveness and reconciliation that Croatia seeks to embody.

“The unification of Europe is basically a Christian project,” Josipovic said, as a military parade and Croatians in traditional dress greeted the pontiff on the tarmac. “It is precisely because of these deep Christian roots of the Croatian people that I am convinced that our citizens will support in the vast majority our accession into the European Union.”

Yet a simmering anti-EU sentiment among some nationalist Croatians grew in April after the Hague tribunal sentenced wartime Gen. Ante Gotovina to 24 years in prison for his role in a 1995 military offensive. Gotovina is revered by many Croats for his role in the battle that sealed Croatia’s independence from Serb-led Yugoslavia after four years of conflict.

Analysts have said that while the anger at the sentence was real, it was temporary, and that the greater problem is a weariness and frustration that Europe has given the cold shoulder to Croatia throughout the negotiation process.

“It’s that proverbial carrot that seems to be constantly out of reach,” said Ivo Banac, emeritus professor of history at Yale University and a Croat. “It’s there, you’re following it, but you can never manage to bite it.”

The Vatican and Croatia, which is 89.8-percent Catholic, have long had solid ties: The Holy See was one of the first to recognize Croatia when it declared independence from Serb-led Yugoslavia in 1991, and the Vatican is eager to have another stalwart Catholic country in the EU bloc.

After meeting with top Croatian leaders Saturday, the pope carried his message about values and Europe’s Christian roots to Croatian politicians, academics and businessmen gathered inside Zagreb’s ornate 19th century national theater. He spoke about the role that free conscience plays in democracies and how, if allowed to flourish, it can be the “bulwark against all forms of tyranny.”

Later, as rain gave way to a cool, clear evening, Benedict drew tens of thousands of enthusiastic young Croats to Zagreb’s central square for a prayer vigil that featured testimony from two young Catholics. The 84-year-old Benedict, who seemed in fine form after such a long day, told the adoring crowd to not be tempted by “enticing promises of easy success.”

“Do not yield to the temptation of putting all your trust in possessions, in material things, while abandoning the search for the truth which is always ‘greater,’ which guides us like a star high in the heavens to where Christ would lead us,” he said.

On Sunday, Benedict will celebrate Mass and then pray before the tomb of Cardinal Alojzije Stepinac, Croatia’s World War II primate whom John Paul beatified during a 1998 trip.

Stepinac was hailed as a hero by Catholics for his resistance to communism and refusal to separate the Croatian church from the Vatican. But his beatification was controversial because many Serbs and Jews accuse him of sympathizing with the Nazis.

Benedict praised Stepinac as a model for having defended “true humanism” against both the communists and the Ustasha Nazi puppet regime that ruled Croatia during the war. The Ustasha, said the German-born pope, “seemed to fulfill the dream of autonomy and independence, but in reality it was an autonomy that was a lie because it was used by Hitler for his aims.”

___

Trisha Thomas in Zagreb and Dusan Stojanovic in Belgrade contributed.