Legend has it that in November of 1621, English settlers in Plymouth and the Indigenous Wampanoags celebrated their newfound friendship with a feast: America’s first Thanksgiving. History, however, tells a story of massacre, war and violence between the Native Americans and the English — that story is much harder to feel ‘thankful’ for.

Besides representing the 400th anniversary of the first Thanksgiving, this November also marks one year since the University of St. Thomas Land Acknowledgement Committee recommended to senior leadership an official statement acknowledging that the campus stands on stolen Dakota land.

“We can’t just make a Land Acknowledgement and then wipe our hands and say that we’ve done our work,” expert in Native American History Stephen Haussmann said. “This is an ongoing process that really ends in material change. Dinner table discussions about Thanksgiving and Native American history is part of a process of change.”

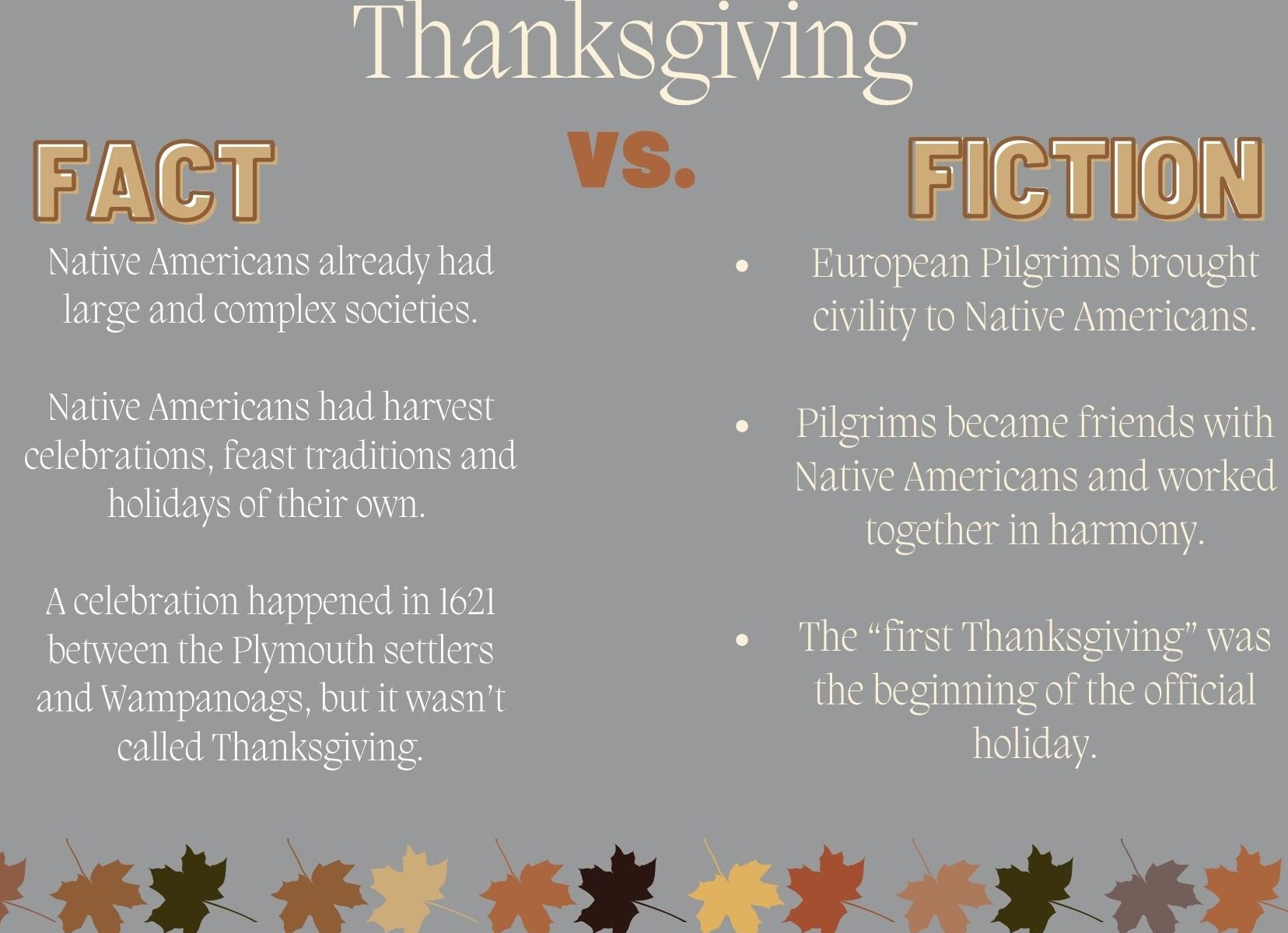

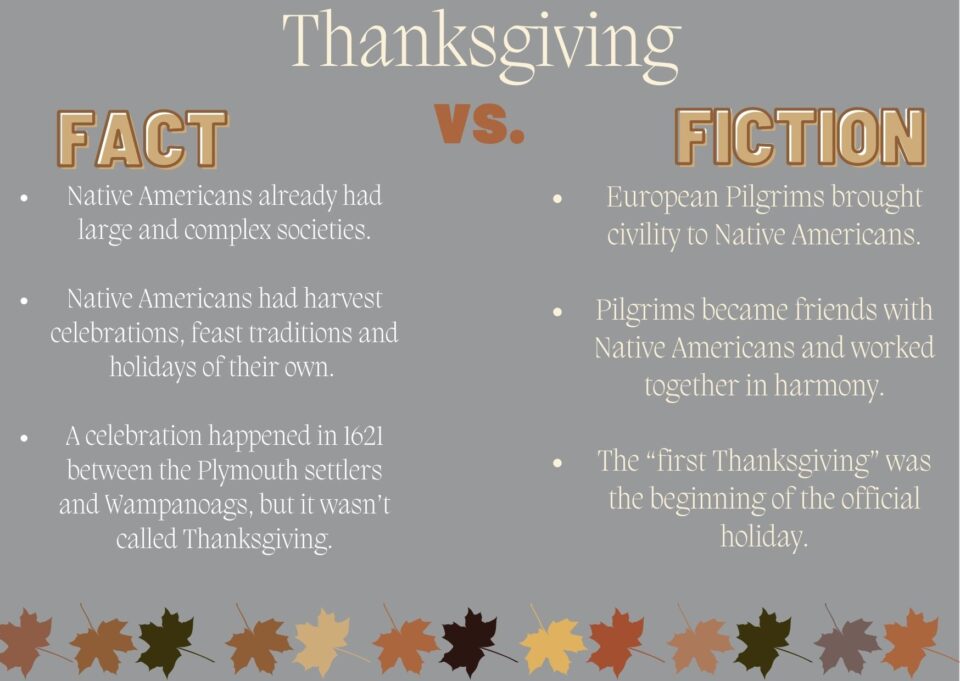

Haussmann, a St. Thomas professor, argued that although myths are part of human society, separating fact from fiction is a crucial part of an ongoing process of transformation.

“If anything, the Land Acknowledgement requires us to go further,” Haussmann said.

Separating history from myth

In 1841, Reverend Alexander Young wrote a book about the history of the Pilgrims and mentioned the idea of the first Thanksgiving; the story took on a “life of its own,” Hausmann said.

Hausmann said that despite popular belief, all the traditions associated with Thanksgiving were created in the decades that followed.

“(Americans) have completely overwritten or erased the much more complicated history of what this particular moment in the 17th century was all about: English people settling and colonizing a place that did not belong to them,” Hausmann said.

The real history of the so-called first Thanksgiving day completely deviates from the myth of the peaceful, friendly feast celebrated by the Native Americans and settlers.

The Wampanoag people were not invited to the original event, Hausmann said.

While the English were indeed having a day of thanksgiving, the Native Americans only arrived because the English were firing their guns in the air in celebration and the Wampanoag thought violence had broken out. Eventually, the Wampanoag people were allowed to stay and share food with the settlers.

Yet 1621 was not the only year the English celebrated a day of giving thanks that included the Wampanoag people.

A day of thanksgiving was held after an English victory over the Wampanoag in 1876. In celebration, the Pilgrims mounted the head of the son of a Wampanoag leader on a spike, Hausmann said.

“Violence is as much a story of the older history of Thanksgiving as much as getting together and feasting is,” Hausmann added.

Fostering honest conversations on campus

The university is currently seeking to educate students on the Land Acknowledgement’s relevance through programs and events that encourage discussion about Native American culture, said Alex Hernandez-Siegel, director of Student Diversity and Inclusion Services and member of the St. Thomas Land Acknowledgement Committee.

“We’re taking students to a restaurant in Minneapolis in which they serve indigenous food pre-colonial times … the theme (Native American history) is always there.”

Although the University of St. Thomas did not organize an event to foster discussions on the history of Thanksgiving this year, Hernandez-Siegel recognized the importance of discussing Native American heritage in the context of colonialism and said that in the future, such conversations could be arranged by the institution.

“Thanksgiving really has this one-sided notion about celebrating how individuals came here from England seeking a new start and that they harmoniously met with the indigenous community here,” Hernandez-Siegel said. “But in the end, indigenous people really suffered from it … their communities were wiped-out.”

History is not only about the past – it can affect the future through transformational change. One way of doing that was through the Land Acknowledgement, Hernandez-Siegel said, which has become a model for other institutions in the U.S. and even Canada.

“Our Land Acknowledgement is different than most I’ve seen,” Hernandez-Siegel said. “Here, we go further to say actually what happened, engaging in truth-telling, and our responsibility as a community to look in terms of our education of students to end that legacy of violence. It’s more than just history.”

While organizing events, creating programs and releasing a Land Acknowledgement statement are part of the process, fostering real dialogue about the history of Thanksgiving can also be a way of engaging in the path to racial justice.

“If you are, for instance, sitting at your dinner table and some uncle starts to talk about the history of the first Thanksgiving,” Haussmann said, “this is your moment to kind of speak up and say ‘well, actually, the real history of Thanksgiving is much more complicated than that.’

Understanding the reality of Thanksgiving as opposed to the myth is one way students can help students enact positive change in their own circles, Hausmann said.

“So educate yourself and when you hear people talking in terms of these myths point out that that is not in fact the history,” Hausmann said. “That’s one actionable thing that I think historical knowledge requires us to do.”

Luana Karl can be reached at karl2414@stthomas.edu.